working-paper

April 4, 2024

Energy Europe – From integration to power

Europe is fragile. It's a fact: it will never have total energy independence. How can we take advantage of this situation? Pierre-Etienne Franc, co-founder, and CEO of Hy24, proposes to turn a weakness into a strength: to the benefit of the Union's industrial and foreign policies.

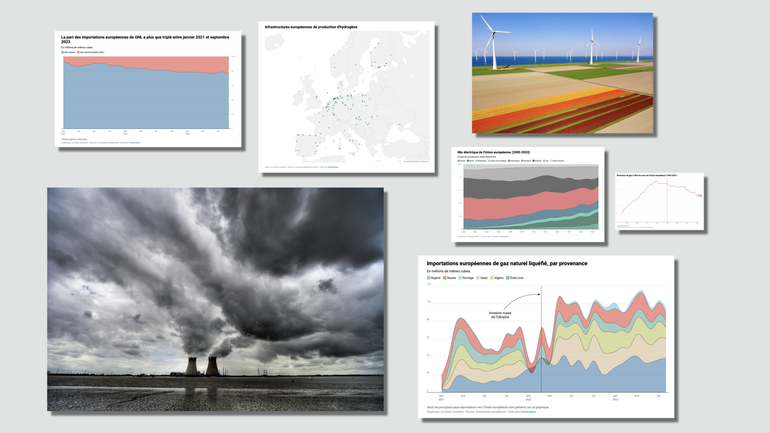

The Ursula von der Leyen “geopolitical” Commission had a structural axis and a framework: the Green Deal. Her term in office began in December 2019 with the presentation of this set of initiatives and the adoption, in 2021, of the Fit-for-55 strategy, displaying a clearly asserted European ambition on climate. Despite the various crises the Union has experienced — from the pandemic in 2020 to the invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 — this approach, rather than being restricted, has paradoxically been strengthened by the return of war to European soil, which has highlighted the close connection between dependence on fossil fuels (which account for over 70% of our energy needs), political sovereignty (over 60% of our energy is imported), and economic competitiveness (energy resources are totally dependent on fluctuations in raw material prices, which we cannot control). By implementing the “RePowerEU” emergency plan in response to the necessary phase-out of Russian gas, Europe has further strengthened its efforts to move towards a low-carbon, more sovereign energy model.

The shift to a low-carbon energy model begins

By combining urgency — guaranteeing industrial production and household heating — with the pursuit of a long-term agenda, Member States have so far successfully navigated the shift away from energy models dependent on Russian imports towards several supply sources, including US LNG. This has been achieved at the cost of significantly higher market prices for electricity and gas, which have probably contributed to accelerating the reform of electricity markets, and increased pressure for a more rapid build-up of the continent’s renewable energy sources, which, at current rates of progress, are set to increase in capacity from 500 GW to 900 GW by 2030. Finally, it is likely that the energy crisis triggered by the Russian war has given further weight to French arguments for revitalizing the nuclear industry and making it practically neutral with renewable energy sources, even if the timeframe for its roll-out and its total cost remain significant unknowns.

In 2023, Europe also continued to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 3%, bringing the total reduction since 1990 to 32.5% 1 . The share of Russian gas imports has fallen from 155 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2021 to less than 50 bcm in 2023. Coal imports from Russia have been completely halted, while oil imports have been reduced by 90% 2 compared to their pre-war levels. More broadly, efforts to reduce energy consumption have decreased dependence on natural gas by almost 20%. The Union has also achieved the feat of coordinating a number of group purchases of gas between countries in order to secure the best prices, representing almost 30% of the continent’s needs, or 44.7 bcm in 2023.

The development of renewable energy projects has not stalled, despite rising costs and interest rates, which have made the sector less attractive. In 2022 3 , more than 40 GW of new solar capacity was installed (60% more than in 2021), and offshore and onshore wind power capacity increased by 45% over the year. The share of renewable electricity in Europe’s electricity mix has exceeded 39%, and May 2022 saw renewable solar and wind power generation overtake fossil-based generation. Today, the share of renewable energy in Europe’s energy mix is close to 22%, and the target of 42.5% by 2030 is still achievable, even if the next stages will be much more complex to implement, as they will involve the decarbonization of the most energy and capital-intensive sectors: transport and heavy industry in particular. Implementing these objectives on a national scale appears extremely difficult for some countries 4 . Significant funds are needed to upgrade transport and electricity distribution infrastructure, which is set to double in size over the coming decades. The costs and investments associated with changes in industrial processes or even engine technology in the transport sector also need to be taken into account. At the European level, the total investment needed for infrastructure and transport to switch to a low-carbon model is estimated at an average of 335 5 billion euros per year over the period 2021-2035 6 , which is equivalent to 2.3% of the Union’s annual GDP.

Report: Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engines in Europe’s Road Mobility Decarbonisation

The development of this report was led by members of the H2Accelerate collaboration which has been formed by major players from the fuel supply and trucking industries to work together to accelerate the deployment of hydrogen - powered trucking in Europe.

More about

“Fuel Cell Technology has now reached unprecedented performance”: Recent Advances Reinforce the Case for Hydrogen Mobility

An interview with Sae Hoon Kim, engineer, leader of Hyundai’s hydrogen strategy and Head of Fuel Cell Development for 20 years.

More about

Innovating to finance the hydrogen economy

On the road to a more sustainable economy, we need more investment in sustainable assets. These investments must not only be supported by appropriate regulatory frameworks, but also encouraged and facilitated by financial mechanisms.

More about